A Vision for the High Calling of Investing

By intentionally reminding ourselves of the true purpose of investing, our hearts are directed outward to our neighbors near and far.

Our investment dollars can shape the world—and our hearts— for good or ill.

By Dr. Amy L. Sherman

Not long ago I heard about a Christian college that had remodeled the building housing its business school. The bright, airy structure boasts a multicolored LED ticker tape display running lengthwise high along one wall on the top floor. At any moment, students and faculty can consult it to learn the ever-changing price of the stocks publicly traded on Wall Street.

I have few doubts that the school is a good one, genuine and earnest in its desire to nurture ethical, competent business leaders whose faith shapes their approach to their work. But installing the ticker tape display was a bad idea, an action at cross purposes to the university’s good intentions. The school seeks to inculcate a Christian world-and-life view, that graduates might engage our society as salt and light, as agents of flourishing. It takes seriously God’s Big Story, the biblical metanarrative of Creation-Fall-Redemption-Restoration that gives meaning to reality. And it wants its students to learn how to align their lives with this story, aware that “the world, the flesh, and the devil” offer destructive, alternative narratives—some proclaimed brashly, others whispered subtly. Sadly, university leaders seem to have failed to recognize that the ticker display embodies at least three malforming influences from what we might call “the world’s story of investing.”

First, it signals the all-pervasive but wrong idea that the primary purpose of investing is to make money. God’s story of investing tells us something different. Investing is one of the innumerable acts of stewardship humans are called to implement. Investing is part of the “cultivating and keeping” of the Garden that God called his people to in Genesis 2:15. The work of obeying this Cultural Mandate takes many forms, from making art to tending zebras, a literal a to z panoply of occupations. Finance is one of those fields of work. And the purpose of investing is to supply capital to businesses to enlarge their capacity for creating goods and services—and meaningful jobs—that facilitate human flourishing. Investors look for opportunities to cultivate businesses, whether that’s in launching start-up enterprises or helping an established firm to expand. And investors, as stewards, are supposed to discern the quality and character of those businesses. Put simply, in alignment with the call to “keep” the creation, we’re not to enable the production of harmful goods and services—even if we could make money by doing so.

Second, it suggests that investing is primarily a numbers game. The stock ticker doesn’t even spell out the names of the companies. It provides symbols instead, and it can be difficult for those not immersed in the field to tell which symbol stands for which corporation. What’s really of interest are the numbers indicating the price of shares. Once again we’re being told that the important thing isn’t what these firms are doing or not doing in the world, but whether or not their share price is increasing. Moreover, these symbols and numbers mask the human beings behind them. We don’t see the people involved, the employees, the customers. The ticker display hides the reality that our investing activities are significantly influencing the lives of real people in real places. It distances us from them; it abstracts this whole exercise. It encourages us to think that we’re investing in “The Market,” this opaque machinery in which we feed our dollars in at one end, and—hopefully—take out even more at the other end.

Third, the ticker display encourages a short-term perspective in our thinking about investing. It provides minute-by-minute accounting of the financial performance of the companies listed. Clearly, it is necessary in our complex global economy to have ways of communicating information to buyers and sellers about how businesses are performing, and share price can be one helpful indicator. But if investing is primarily about helping good businesses produce good in the world, investors likely need to link arms with the on-the-ground entrepreneurs and business leaders for a reasonable amount of time. It takes time for firms to get established. It takes time for companies to learn, innovate, grow, and adapt.

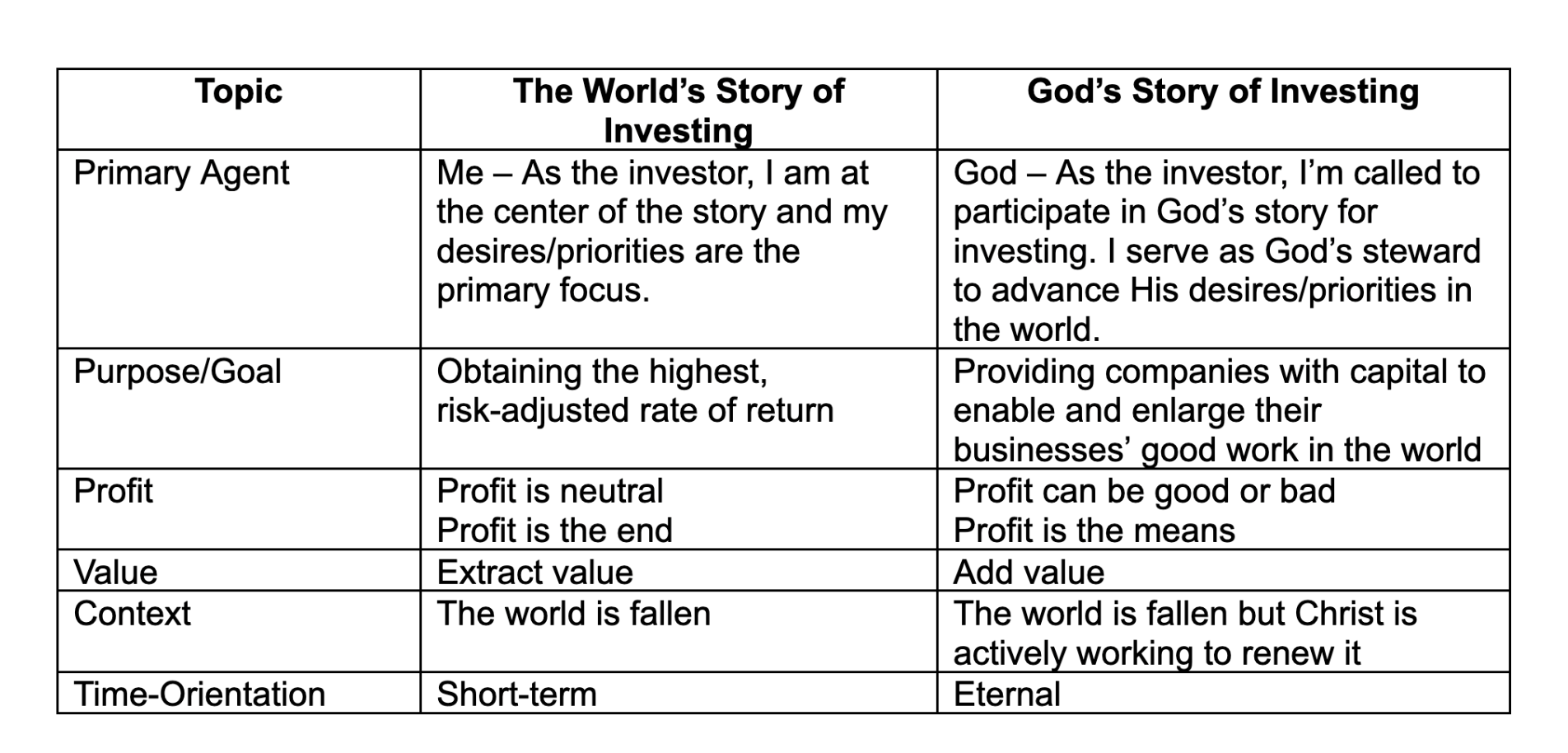

God’s story of investing counters the world’s story at these three points—and others. Chart A below captures several dimensions of difference.

Chart A. Comparing God’s Story and the World’s Story of Investing

Investing according to God’s story turns our focus upward and outward. We are reminded that the funds we’re investing belong to God. This can be a challenge, as we’re tempted to think it’s our hard work or our careful budgeting that have created the disposable income to devote to savings and investing. As we take those funds and seek to offer them as instruments to God in advancing his good purposes in the world, we are proclaiming that God is the one who has enabled us to gain this wealth (Deut. 8:7-8).

Taking this action is also another way of saying (along with the ancient liturgists): “All things come from you, O Lord, and of your own have we given you.” God wants us to deploy wealth in ways that indicate our trust in him as our caretaker, that reveal our confidence in his promise that in blessing others through our stewardship, we will ourselves be blessed.

God’s story reminds us that his purpose for our investing involves our neighbors’ good as well as our own. Investing is a powerful way of expressing the Cultural Mandate. By pursuing investment that promotes the common good, we make the world better for ourselves and others. This is because God has designed the world such that our flourishing is tied up with our neighbors’ flourishing.

God’s story teaches us that it matters what we empower to be made through our investments. This is why profits are not neutral. Profits that emerge from products or services that are not in keeping with the beauty and goodness of God’s creation are not good profits.

The world’s story of investing assumes a world of scarcity and ruthless competition. By contrast, God’s story is that he is active in our world, renewing all things—including the fields of finance and business. There are opportunities for win-win economic exchanges now, and a promise for fully redeemed economies in the New Jerusalem. With our eternal perspective, Christian investors can act from hope and love rather than from fear and greed.

Investing and Our Hearts

Investing is about more than money, but obviously involves money. That means that it has power to act on our hearts. Jesus taught clearly that his followers must be careful and shrewd when handling wealth. Mammon sings siren songs that can lead us astray. Our hearts and our treasures have an intricate relationship. In the field of finance, as I explained in a recent essay, our hearts “act on” on our investments and our investments also “act on” our hearts. As the example of the ticker display shows, when our investments are guided by the world’s story of what investing is, it can malform our hearts. This is because the contemporary finance sector is loaded with assumptions, images, rhythms, and practices—what philosopher James K.A. Smith calls “liturgies”—that have power to influence our desires and inclinations. That’s the bad news, and as investors seeking to be faithful to Christ, we must be diligently alert to these dangers.

Investing that Nurtures Virtue

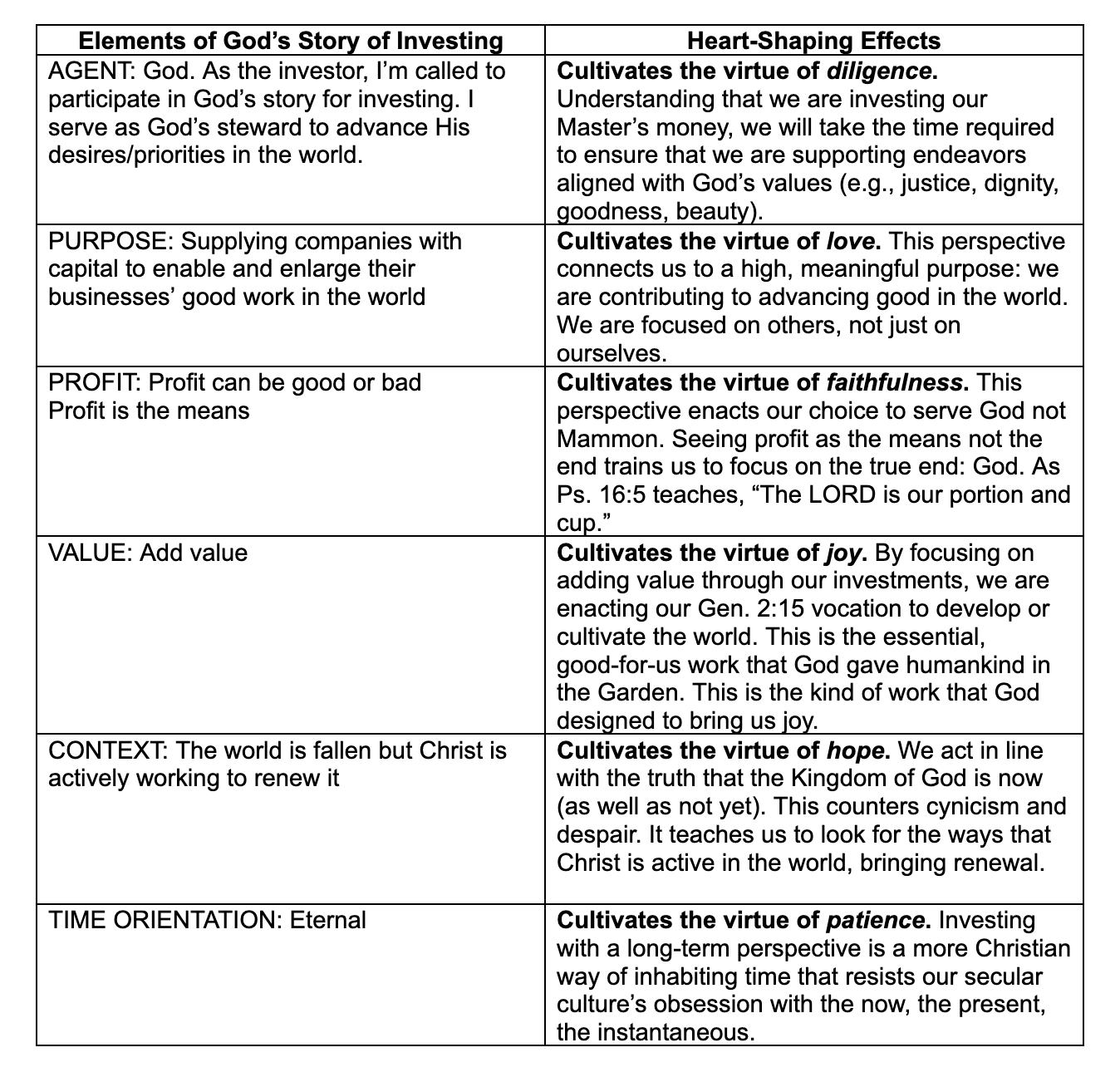

The good news is that investing guided by God’s story can have salutary effects on our hearts. When we are alert to these, the exercise of investing can actually encourage our own spiritual formation. This, ultimately, contributes to the common good. In other words, investing according to God’s story can enhance value in the world and virtue in our hearts. Chart B depicts how our embrace of the “true truths” about investing can nurture a variety of virtues.

Chart B. Positive Effects of God’s Story

Scripture calls us to an earnest pursuit of virtuous character, through the indwelling power of the Holy Spirit. This pursuit requires that we develop habits—specific practices through which virtues can grow. Stewarding God’s money through our investing practices is one expression of this.

Diligence. Taking the time to educate ourselves about God’s mission in the world, about his passions for how things ought to be, and about the companies in which we are considering investing is a practice that grows the virtue of diligence in us. We resist the temptation to take the easier route of assessing companies solely on their financial performance or just jumping on the bandwagon of whatever mutual fund is listed as “hot” by media outlets.

Admittedly, investing is complex and average investors lack expertise. Most of us don’t have the time required to become experts. Yet anyone can take the three practical steps of diligence described below.

- Examine the fund’s prospectus for clues to the criteria and values by which companies are selected for inclusion. Prospectus documents are a little intimidating in their length and jargon. Browse through them online, paying attention to sections titled “investment strategy” or “investment case.” Use the CRTL-F (“find”) feature and look for words like “ethical” and “values.” You are trying to learn whether the fund manager’s judgments are based solely on financial factors (e.g., predicted returns, market conditions, considerations around the size of the firms). Is there any evidence that company inclusion in the fund is based at all on particular firm practices (e.g., in the area of governance, employee care, or environmental sustainability)? Are there any ethical screens being used to avoid businesses that are engaged in harmful activities (such as gambling, pornography, payday lending, or tobacco)?

- Educate yourself about the “brand promise” of different asset managers. Choose companies that (a) incorporate ethical factors when selecting businesses to include in their investment products and (b) provide information or profiles of at least some of the companies in their ETFs or mutual funds. I’m heavily invested in a funds manager that includes a “how we invest” description on its website, listing the company’s values and the ethical screens it deploys. It also has a “news and stories” section online where I can read about the activities of the companies in their mutual funds and how those businesses are making a positive impact in their communities and sectors.

- Wisely select a financial advisor. My friend Jason Myhre at the Eventide Center for Faith and Investing notes that parents who decide to hire a nanny probably take some time to look for candidates who share their parenting and discipline philosophy. After all, for those hours when they must be absent from home, the parents likely want someone who shares their values to tend their kids. Similarly, given our responsibility as stewards of God’s resources, if we are going to turn some of that responsibility over to another person, shouldn’t we want to know something about their investing philosophy? We need to ask whether this person will make decisions that align with how we would make them, using the same kinds of criteria. One way of ascertaining this is to tell a prospective advisor about our own values and interests. We can also tell them that in our meetings, we wish not only to hear a summary of our portfolio’s financial performance but also something about what our money is accomplishing in the world through the companies it is helping to fund. We could, for example, request that the financial advisor tell us one story at each meeting about a specific firm in our portfolio, answering questions like, What goods and services does that firm provide? What’s known about its record in respecting its customers, employees, and the creation?

Love. By intentionally reminding ourselves of the true purpose of investing, our hearts are directed outward to our neighbors near and far. We will see ourselves as playing a role in the large “circulatory system” of finance, with our dollars enabling businesses to do their important work of producing goods and services and providing jobs. We will understand that our investing sets us into a web of relationships, rather than considering it an abstract, mechanical act. This reminds us that our actions have consequences in real people’s lives. By making their welfare part of our calculations, we put agape love into action. That love is further encouraged when our review of our investments includes attention to their social, as well as financial, impact.

For me, this looks like reading the literature produced by asset managers I’m invested with, such as annual reports that highlight the activities their portfolio companies are engaged in. In this way, I learn about why the sectors these companies are located in matter for human flourishing, what contributions these companies are making within their sectors, and how the products or services they provide effect real people and real communities.

Faithfulness. Investing according to God’s story reminds us that profit is a means to an end, not the end itself. When we make investing choices based on that mentality, we slay the idol of Mammon. Mammon wants us to believe that wealth will make us secure, that wealth is our protector, that it is the inheritance we need to be safe in the future. But God wants us to know that he alone is our true security, protector, and inheritance. Proverbial wisdom does encourage us to save for the future. But saving can become hoarding, a fearful accumulation of money we come to believe will buffer us from future harms.

I recently made a second investment in a social enterprise in Kenya that employs poor mothers, training them in sewing and other textile-related skills. The company, a few years past start-up, is struggling some and issued another call for capital. As a single woman without children, I’m a little nervous about whether I’ll see my capital returned in the future. But the enterprise’s social impact is considerable, and the founder runs the business with values I wholeheartedly embrace. This investment, which represents a portion of my “retirement fund,” is helping me learn to trust that God will be my provider when I’m no longer able to work.

Joy. God finds delight in the works of his hands. Proverbs 8:30-31 describes the Trinity’s joy in creating the world. God commissioned humans to bear his image by engaging in creative labor. We do not create ex nihilo; rather, we discover and develop the latent potential of creation. We find ways to add value. Importantly, we do this while also guarding or “keeping” creation. Our posture towards the earth and towards others is not to be extractive. When we do work that adds value, we are living into our commission, and like God, truly experience joy in that work. When we invest according to God’s story, we offer capital that can strengthen, expand, or diversify businesses, enabling them to do more good in the world.

One of my investments is in a publicly traded, themed mutual fund that focuses on water-related businesses. I’m pleased that it has doubled in value since its inception in 2008. I’m delighted that the companies that make up the fund are innovating ways to conserve water, clean wastewater, transport water to where its needed, and improve public health by increasing the quality of water infrastructure systems. In the past, I’ve used my charitable dollars to support the digging of individual wells in poor villages in Africa. Seeing the photographs of smiling women and children enjoying their new community well brought me joy. But so does knowing that I play a small part in a giant ($548 million dollar) endeavor that is harnessing the power of business to improve the lives of hundreds of thousands of people.

Hope. A truly biblical conception of hope is closely connected to joy. Christ-followers have hope in this fallen world because of the sure, joy-filled future God has promised. Christ has already inaugurated his kingdom and has promised to bring it to completion. The Trinity is active in this world, now, bringing renewal. These facts help us press against the pervasive cynicism of our culture.

We further nurture the virtue of hope when we make investments that bear witness to the fact that new creation has arrived in the midst of the old. These are investments based on the idea that win-win economic transactions are possible, that not everything is a ruthless, zero-sum competition. These are investments that lean into risk for the sake of introducing innovations in the world that accomplish wondrous things: revolutionizing agriculture and healthcare, connecting isolated households to educational and commercial opportunities, and bringing healing to individuals suffering mental and physical illnesses.

Patience. Many practices in our culture today erode the virtue of patience. We have 24/7 access to activities that once were more limited, such as shopping or banking. We have nearly instant access to news. We can find answers to many questions with just a few clicks on our smart phones. Our technology gadgets facilitate instant gratification. All of this can engender impatience regarding our investments. We desire quick returns. We ditch a stock after a few months in favor of another promising higher alpha.

This short-term perspective is nothing like God’s eternal perspective, which he enjoins us to share (2 Cor 4:18). Deliberating making long-term investments or providing “patient capital” to new businesses puts us into a slower, counter-cultural rhythm. “Buy and hold” should not be a straitjacket, in which we cling for years to failing companies. But it is simply a fact that doing good in the world through commercial endeavors is often a long-term proposition. I’m currently researching long-term municipal bonds because I like the idea of supporting infrastructure and public works projects at the community level. Being open to the 10+ year time horizon on some such bonds offers me a way of practicing the catalytic potential of patient capital.

From Passive Investing to Active Stewardship

I suspect that many faithful Christ-followers are like the leaders at the Christian college who decided to include that marquee ticker display in their new business center building. They desire to conform their character and work to biblical truth. They want their faith to shape how they act in the world. They want to honor Jesus with their money. But when it comes to investing, they have not given much thought to how the “conventional wisdom” offered by the world undermines faithful stewardship. Like their nonChristian neighbors, they’re simply looking for a good return.

The problem is that our investments are not neutral. They affect real people in real places. They have the power to increase or diminish human flourishing. As God’s stewards, we are called to use his resources to the best of our ability in ways that align with his good purposes for the world.

This requires effort and intentionality. And it can be frustrating because this world is fallen. No business is perfect. No mutual fund can guarantee that every action taken by every company in its portfolio will be honorable and just. The world of investing is complex. We can’t know everything we might want to know. But these challenges and limitations do not excuse us from the duty of diligence. After all, it is God’s money that we are managing.

In the face of these realities, I’ve found hope and comfort in Steve Garber’s teaching on proximate justice. In his book Visions of Vocation, he writes that it is “an old idea…taken up by people who in their own times and places have longed to do what is right, knowing that all that is right will not be and cannot be done.” The idea is necessary because “the world is a hard place to live, but there is nowhere else to live. So if we are going to be honest, we have to live with what is proximate.” With investing, this idea of proximate justice calls us to do what we can do, knowing that what we do is never enough, never can be enough. It encourages us to recognize our responsibility to eschew passivity, to refuse to drift along the easy path of “careless” investing—that is, investing with no thought whatsoever to what our actions may mean for our neighbors.

After 20+ years working for the same organization, I am fortunate to have a retirement account to which I have contributed monthly, and those contributions have been matched by my employer. This is no small benefit; literally billions of people on the globe have nothing of the sort. I feel grateful for it, as I should, and I believe it represents one way God has provided for the future when I will no longer be capable of working. At the same time, I’ve had almost no control over how this money has been invested. As an employee—like many employees—I have been presented with a fait accompli. Other people have made the decisions about which investment managers to use, which mutual funds will be offered, and which companies will be included in those funds. I’m frustrated by this, and I lament it. That is one part of what the wisdom of proximate justice teaches me to do. I learn what I can and make the best choices I can within these restricted parameters. The other part is that, with additional money I can invest and have more agency over, I do my best to research options. I look for opportunities invest in companies with good practices and good products. I seek out social enterprises to support. I look for ways I might lend capital to endeavors aimed at doing things I’m passionate about: creating jobs, building needed infrastructure and affordable housing, helping communities and companies transition to green energy.

Being Alert to Heart Effects

Our stewardship decisions not only affect our neighbors near and far. They also have power to either deform or nourish our own hearts. The reality is that investing according to the world’s story can feed our fallen inclinations toward greed, control, fear, self-centeredness, and impatience. Yet, practicing investing informed by God’s story can be a means of spiritual growth. I find that quite surprising. After all, despite attempts to avoid dualistic thinking, I can fall into the habit of thinking that only “spiritual” activities—praying and reading scripture, for example—produce “spiritual” benefits. In fact, all kinds of habits, including what actions I take with the money God’s entrusted to me, can aid me in the pursuit of Christ-likeness. When I think about my investments’ ROI, I’m learning to look for a harvest of virtue.

[Dr. Amy L. Sherman serves as Editor-At-Large of The Journal for Faith & Investing, and is a Senior Fellow at the Sagamore Institute. She is the author of Kingdom Calling: Vocational Stewardship for the Common Good and Agents of Flourishing: Pursuing Shalom in Every Corner of Society]